The York City riot: When the world woke up to problems at Brighton

“Did I miss much then?” Good question. My mother was lying in a hospital bed at the Royal Sussex, recovering from an operation on the ankle she had broken playing football in Hove Park, as you do.

For the first time since I had been born eight years earlier, she had been forced into missing a home game at the Goldstone Ground. It was Saturday 27th April 1996 and she was asking what had happened in the Division Two match between Brighton & Hove Albion and York City.

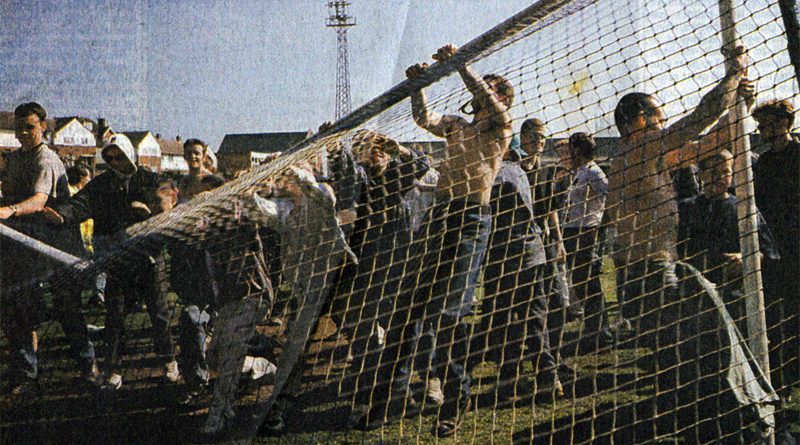

With no internet or mobile phone, she was blissfully unaware that the game had in fact lasted only 16 minutes before both crossbars had been snapped.

As we sat in the hospital, the Sunday newspapers were preparing sensational headlines about the Brighton riot and a return to the dark days of football hooliganism.

Before we had reached the Royal Sussex, my dad had debated how much we should tell my mum about the riot. T

he reason for this was not because he was worried she would be upset about her husband and young son getting caught up in it. It was because he did not want to make her think she had missed out.

There was little chance of my mother swinging from the crossbar in front of the South Stand in an attempt to break it. She did though despise Bill Archer, Greg Stanley and David Bellotti.

For the next year after her ankle operation, she would take the crutches she had been given to every away game around the country. She didn’t need them, her purpose for having them was purely on the off chance she would get to innocently trip Bellotti up.

Bellotti being the coward he was always managed to avoid the fans. The closest she got was Rochdale away six months after the York game, when a handful of Albion supporters waited for him outside the Spotland players entrance on a cold Tuesday night in November.

Little did we know that he had been smuggled past us all in a kit bag and onto the luggage rack of the team coach, years before Jose Mourinho famously snuck into the Chelsea dressing room using the same trick to deliver a team talk whilst he was meant to be serving a ban.

Anything that might bring about the demise of the Archer, Stanley and Bellotti regime was to be welcomed.

When my father finished explaining the events of our Saturday afternoon at the Goldstone, she was surprised and a little bit saddened it had come to this. But the general consensus was that it would at least bring some attention to Brighton’s plight.

It certainly did that. Before the York City riot, nobody on a national level seemed remotely bothered about what was happening at the Goldstone Ground. Afterwards, my mother could watch the action unfold on the BBC evening news, where it was the lead.

Now, the country were being told the story. Archer, Bellotti and Stanley had conspired to remove a non-profit clause from the the club’s rules.

Said clause had stated that if the Albion went out of business, no individuals could gain financially. Any assets and money the club had in the bank had to go to sporting causes in Sussex.

Removing the clause meant the three could sell the Goldstone to developers, drive the club out of business and then pocket the profits from the sale.

They might have got away with it all had Paul Samrah not noticed in the summer of 1995. For the next 10 months, Albion fans had been waging a war against their profiteering board to try and save their club. The trouble was, nobody else with the power to make a difference seemed to care.

The York City riot was meant to be the final time Brighton played at the Goldstone. Chartwell – the new owners of the ground – had given the Albion the opportunity to stay for one further year before they knocked it down.

Archer was yet to agree to pay the necessary funds, even though the FA were refusing to sanction his solution of a groundshare with Portsmouth.

As far as anyone knew on the morning of the game, Brighton v York City was the last time anyone would be setting foot in the Goldstone, so what was there to lose by having a riot? Especially if it brought some attention on the asset stripping of a 95-year-old footballing institution.

“I think the fans conducted themselves with a lot of dignity and control,” former Brighton manager and footballing icon Liam Brady said of the day.

“The scenes on television of York City were not scenes of people intent on mayhem and bloodshed, it was a different kind of riot. Okay, so the goalposts got pulled down but it was out of frustration.”

“It was really fans saying, ‘There’s nothing more we can do, let’s go on the pitch and let people know what’s going on at our club’, but you know that should be to their credit.”

Brady, as always, was spot on. It was a different kind of riot and whilst the media coverage sensationalised the event and the photos of fans swinging from broken crossbars looked bad, there was no violence involved at all.

It was just destruction of property – property which Albion fans had more right to claim that Archer, Bellotti and Stanley. After all, the Goldstone had been Brighton’s home since 1902. Those three had rocked up a few years earlier with the sole intention of running the club out of business.

The police knew some form of protest was going to take place and they allowed supporters to spill onto the pitch from the North Stand and the South West Terrace. Once the goals were snapped in two, there was no hope of the game continuing.

That meant there was no pressure from the police to clear the pitch and restore order to get the game restarted, allowing the riot to take its course and the most unlikely of rioters to enjoy themselves.

For what the media did not show were the group of old ladies who were sat on the halfway line, chatting as if they were at a picnic rather than a riot. My friend and I had a miniature football to kick around on the pitch for an hour after the game was forcibly abandoned.

You did not see that when Chelsea had been on the rampage back in 1983, the last genuine riot at the Goldstone when Blues’ player Chris Hutchings managed to get himself arrested.

Even the York fans were supportive. They had undergone a 500 mile round trip to watch 16 minutes of football, but could be heard chanting “Archer Out” in support whilst the riot was taking place.

This was more than just about Brighton; unscrupulous owners could happen to any club and English football needed to wake up and realise that the situation in Sussex could easily occur elsewhere in the country.

Suddenly, the Albion were all over the media. The Brighton v York City riot was discussed on Match of the Day. As well as leading the BBC news, it dominated Radio 5 Live and was in every single newspaper the following morning. The coverage was global.

The timing in a way was perfect. Euro 96 was set to start a little over a month later, and suddenly there was panic that England’s first chance to hold a major tournament for 30 years might be marred by the sort of football fan behaviour the country came notorious for through the 1970s and 1980s.

Some media outlets were at pains to sensationalise it to that level – the News of the World being chief in that, unsurprisingly.

“Rampaging fans turned Brighton into a war zone yesterday in sickening scenes that shamed soccer,” they reported.

“The Goldstone Ground erupted into violence as thousands of fans stormed across the pitch – smashing both sets of goalposts and forcing the game against York to be abandoned after just 16 minutes.”

“Terrified parents rushed crying children to safety,” read one of the more fabricated details from a reporter who must have been at a different match to the rest of us.

Other media sources though sought to discover just why the normally genteel people of Brighton & Hove had gone on a rampage, destroying their home ground.

They then tried to explain the justification behind it, to alleviate fears that Euro 96 could suffer the same fate. Once the real reasons for the York City riot became clear, the wider world was awake to the plight facing Brighton.

It is probably fair to say that, at the time, nobody quite realised just how important the York City riot would be in the battle to save Brighton.

Looking back, you can make an argument that it was the turning point. Albion supporters had now shone a spotlight on what was happening, one which the FA and the rest of football could longer ignore. Support began pouring in from fans of other clubs.

The following morning, Brady was stood in Hove Park saying he had put together a consortium willing to take over from Archer, Bellotti and Stanley. He was also offering to personally pay the rent to Chartwell to keep Brighton at the Goldstone for one more year.

Before the York City riot, there had been no hope for Brighton. In less than 48 hours, a glimmer existed – somebody wanted to end the ownership nightmare, we could stay at the Goldstone for one final season.

And most importantly of all, the pressure on Archer, Bellotti and Stanley was cranked up a notch as the whole world now knew what they were up to.

So, yes mother, turned out you missed quite a bit that day.